UI art museum to build on decades of brilliance

By the 1960s, the University of Iowa had long been known as a leading university for the arts.

“The art being made on campus at that time was breaking all sorts of boundaries,” says Lauren Lessing, director of the UI Stanley Museum of Art. “We were known as one of the hottest avant-garde art programs in the world.”

Along with creating art, the university also had amassed an impressive art collection that included works such as Max Beckmann’s Karneval and Jackson Pollock’s Mural. However, these valuable pieces did not have a permanent home. They were scattered across campus and often hung in haphazard places such as student painting studios and above the circulation desk of the Main Library.

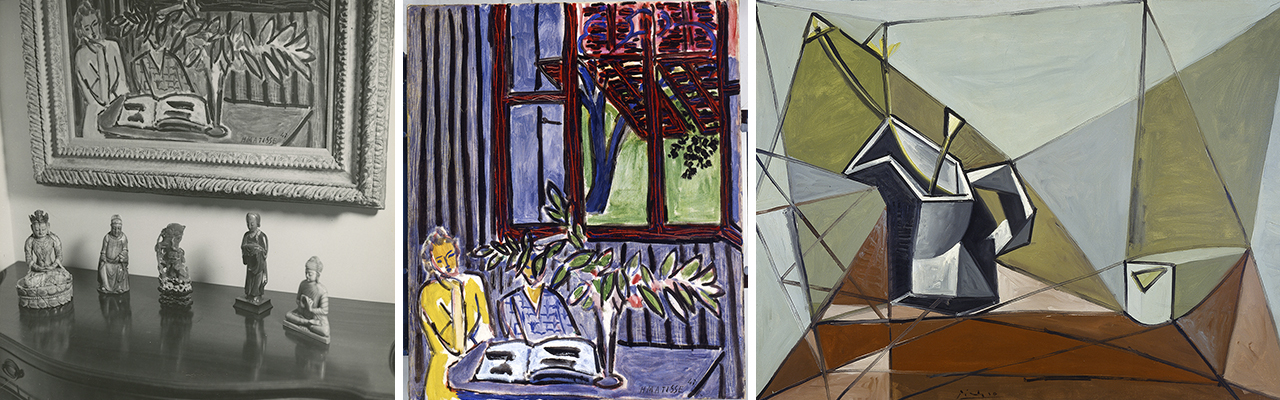

In 1962, a Cedar Rapids couple offered the UI their art collection—1,200 works that included prints, sculptures, and paintings by the likes of Picasso and Matisse—on one condition: a museum would be built to house it.

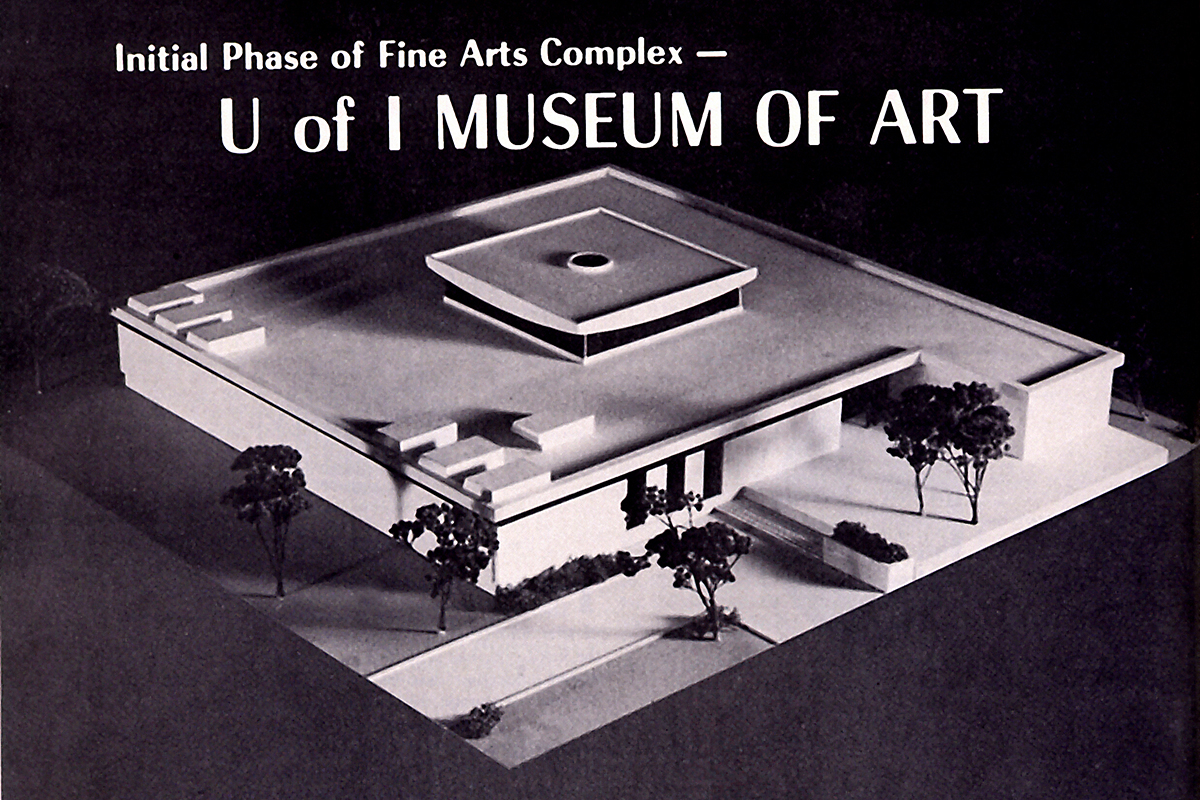

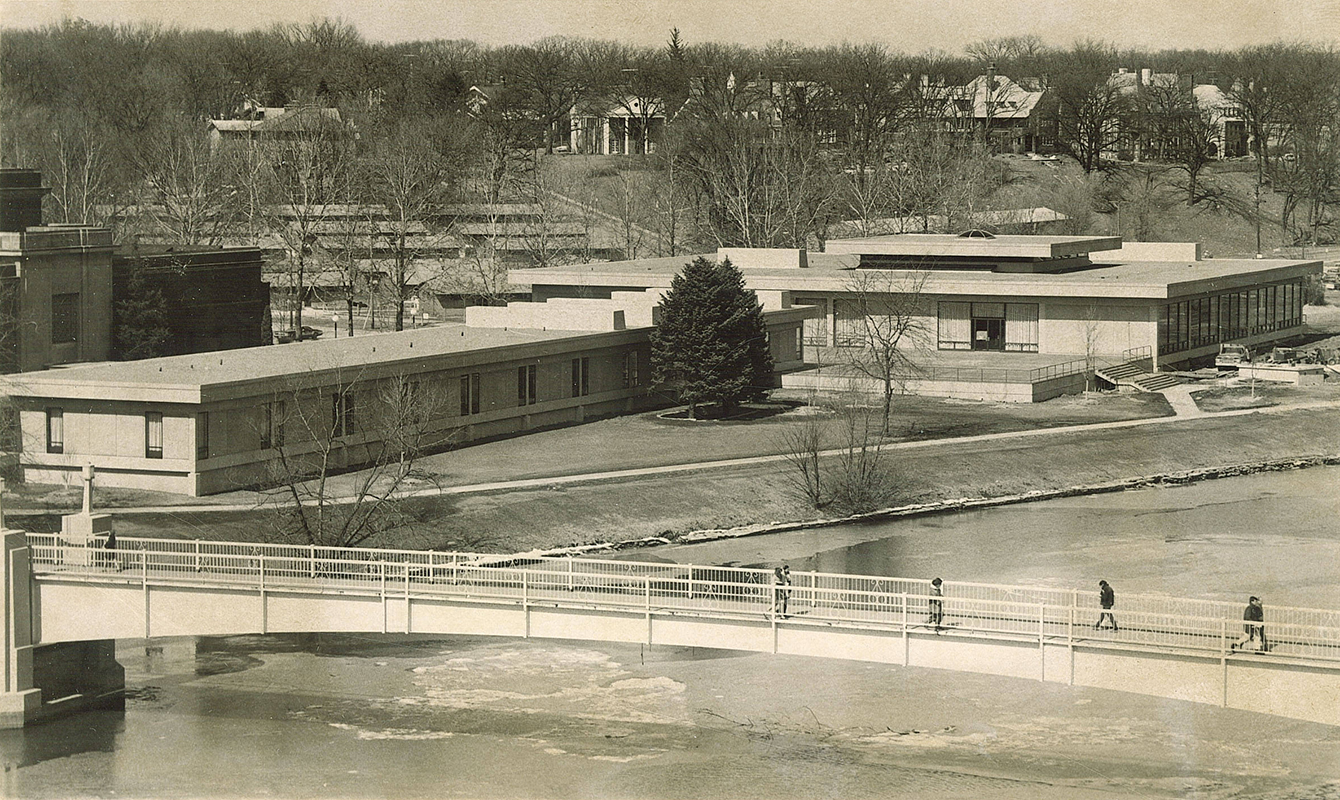

Iowans rallied, and in May 1969, a week-long festival commemorated the completion of the new UI Museum of Art. Built along the Iowa River on what once was the site of a city dump, the prairie-style museum’s four wings surrounded a sculpture court beneath a ceiling featuring an oculus with a sunburst design of concrete beams. It became a hub for the community and campus—the site of first dates, elaborate costumed galas, meetings for drawing clubs, and (of course) hundreds of exhibitions that explored art forms ranging from tattoos to bookbinding, and focused on themes such as political commentary and Victorian fairies in art.

As the state celebrates its art museum’s 50th anniversary this year, it also looks forward to a new building, necessitated after the devastation of the 2008 flood. While much has changed over 50 years, Lessing sees parallels between the two periods.

“1969 was a moment when everything was up for question,” Lessing says. “People were rethinking pedagogy, and they were rethinking the role of universities, and they were rethinking what art was. I see many of the same things happening right now, including a massive paradigm shift for museums, where people are rethinking what a museum is.”

An early leader in the arts

Since the flood, the UI Stanley Museum of Art has magnified its presence throughout the state and across the globe, even without a building. The museum has hosted more art events, launched more educational programs, and reached even more art lovers than ever before. Everyone involved wants to maintain this vital work—and their highly successful outreach programs—far beyond the move into the new building.

But it can’t be done without you.

In the 1920s, UI President Walter Jessup and Graduate Dean Carl Seashore began formulating the then-revolutionary concept of combining studio courses in the practice of art with the history and theory of art—known as the “Iowa Idea.” For centuries, the two disciplines were separate, and taught as such. In 1938, Art History and Studio Art merged into one department, and the “Iowa Idea” became a model for many arts programs across the country.

Meanwhile, faculty member Grant Wood had achieved fame for his iconic American Gothic painting, and, under the direction of modern art advocate Lester Longman in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s, the School of Art and Art History recruited other world-renowned faculty like Argentinian printmaker Mauricio Lasansky and painter Philip Guston, and nurtured a generation of creatives who flocked to Iowa to earn the first-in-the-nation Master of Fine Arts.

Throughout this time, the UI continued to establish an art collection.

Martha Wright Ranney of Iowa City in 1907 established the Mark Ranney Memorial Fund in her will to honor her late husband, who had taught in the medical school. The endowment, which continues to this day, supported the purchase of numerous works of art, including Karneval and Joan Miró’s A Drop of Dew Falling from the Wing of a Bird Awakens Rosalie Asleep in the Shade of a Cobweb.

Longman launched annual summer arts festivals at the Iowa Memorial Union in 1939, bringing world-famous works by top artists to Iowa and creating another pipeline for donations and acquisitions of artwork. By 1951, the UI had established a reputation that led art collector and philanthropist Peggy Guggenheim to donate Pollock’s famed Mural.

While the idea of an art museum on campus had been discussed since the 1930s, lack of funds kept it from being realized—until one couple’s love of art inspired historic action.

The Elliotts enter the frame

An avid print and drawing collector, prominent Cedar Rapids attorney and UI alumnus Owen Elliott had an appreciation for beauty. But nothing ever captivated him quite like Leone Lorimor, a colleague who shared his passion for the arts. During their courtship, Owen encouraged Leone to pursue a degree in art history at the University of Chicago, often joining her for weekend strolls through the Art Institute. On Leone’s graduation day in 1929, the couple married and began traveling across India, Japan, and Europe to build an art collection—and a life together.

Throughout 53 years of marriage, the Elliotts visited art dealers, studios, and galleries around the world to acquire an extensive collection of 19th- and 20th-century paintings, prints, rare jade, and antique silver. They were among the last Americans to leave London before World War II and the first to return to Paris after the fighting was over, investing mere thousands on works by artists such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso that would later become multi-million dollar pieces. Then, in 1956, Owen suffered a severe stroke. Art suddenly turned into more than just the Elliotts’ hobby; it became their hope for healing.

Doctors advised Owen—who lost his memory and ability to walk—to stay home and rest. Yet Leone used her husband’s affection for the arts to restore his health. Beginning in 1958, she pushed Owen and his wheelchair around the museums and art studios of Europe. As they revisited their old haunts, Leone worked to rebuild Owen’s memory. She shared with him the vivid details of their adventures, such as the time a flight attendant threatened to throw the precious Chinese jade they’d bought in Japan out of an airplane during a tropical storm. The jet needed to lighten its load, but Owen resisted: “If you throw that box out, I’ll go with it,” he said, according to Leone’s 1980s interview with Iowa City broadcaster and UI alumna Dottie Ray.

Slowly, Owen’s health began to improve, and the couple continued amassing art together. As the Elliotts began considering the long-term future of their collection in 1962, the UI’s devotion to arts education drew their attention. They invited UI President Virgil Hancher and School of Art and Art History Director Frank Seiberling to their home with a monumental challenge.

A historic campaign

The Elliotts offered the UI their impressive art collection—at the time worth more than $1 million—with a small wrinkle: the university had to raise $1 million to build an art museum where these masterpieces could be appreciated, studied, and preserved under one roof. UI alumnus Loren Hickerson, the director of the UI Alumni Association and newly fledged Foundation, mobilized the fundraising charge, calling their gift “one of the great blessings of university history” that would eventually lead to the arts campus we know today.

The Elliotts’ gift would triple the size of the university’s art holdings. Hancher and Seiberling knew that an investment in the collection would only grow in value over the years, as well as raise the UI’s profile in the fine arts. But the university had a problem: It had never run a major capital campaign before, nor did it have much organization in place to do it. Raising $1 million seemed daunting.

Regardless, Hickerson said the Elliotts put a “burr under the [UI’s] saddle” by placing a July 1967 deadline on fundraising, after which they’d donate the art to rivals at the University of Nebraska with its already-established museum. Hickerson and his team agreed to move forward on the plan to raise the necessary funds—more than the sum total of all the private gifts in 115 years of university history.

Only seven years earlier, Hickerson and the UI Alumni Association had established the Old Gold Development Fund to foster alumni giving, leading to the 1957 birth of the UI Foundation. In 1964, Foundation leader and UI alumnus Darrell Wyrick was charged with guiding the museum campaign that would lay the groundwork for all future university capital efforts. With the Elliotts’ deadline looming, he had no more than two years to accomplish the goal.

The grassroots effort began on campus, where faculty and staff showed their commitment to the project by donating more than $200,000 (twice their original goal). More than half came from the medical school, where cardiology professor and university campaign co-chair Lewis January persuaded faculty to donate $1,000 gifts.

Iowa City–area professionals and businesses matched faculty and staff giving with the leadership of banker and UI alumnus W.W. “Bill” Summerwill. Wyrick then joined incoming UI President Howard Bowen, UI Provost Sandy Boyd, newspaper publisher and campaign chairman Philip Adler, new UI Foundation leader for annual giving Jerry Hilgenberg, UI Alumni Association Director Joseph Meyer, and others on the road to rally support across the state and region. Everyone from schoolchildren to the heads of the Maytag Corporation chipped in what they could to build a great cultural resource for Iowa.

By the end, more than 2,000 people and businesses contributed $1.2 million to construct the $1.7 million, 39,000-square-foot facility.

The museum opens

By October 1966, campaign leaders became confident they would reach their fundraising goal. That fall, Adler proudly turned the first sod for the then-named University of Iowa Museum of Art’s groundbreaking northeast of the Art Building along the Iowa River. To celebrate, the art school hosted an exhibition of selected works from the Elliott Collection.

Museum planners took advantage of a new Board of Regents, State of Iowa, policy that allowed state architectural firms to work alongside nationally recognized design firms on university buildings. Designed by Harrison & Abramovitz—the firm responsible for the United Nations headquarters in New York—the museum established a legacy of partnership matched today by Art Building West, Hancher Auditorium, and the Visual Arts Building.

The UIMA opened in May 1969. The museum featured a central sculpture court with an oculus, permanent and temporary exhibition space, a conservation lab, and a 100-seat auditorium. Volunteers prepared wall labels for the art, polished the Elliotts’ jade with a toothbrush, and baked cookies and cupcakes for the grand opening.

The museum’s opening featured the Elliott Collection:

Five additional exhibitions featured:

The campus celebrated with a weeklong festival representing all the arts. Arts and the Artist, 1969, featured tours of the museum, concerts on the bank of the Iowa River, poetry readings, plays, and film discussions. German artist Hans Haacke presented A Silver Line in the Sky, a performance in which a 300-foot-long strip of Mylar was slowly raised into the sky between two balloons to a height of about 1,500 feet above the riverbank.

“It will be like floating abstract art,” Seiberling said in a 1969 Daily Iowan story. “It will suggest the lifting of spirits on this festival day.”

German abstract expressionist, collector, UI alum, and professor Ulfert Wilke presided over the new institution as its first director. Far from an arts snob, Wilke was an animated mentor who made art accessible to the public and enjoyed close friendships with many contemporary artists highlighted in the museum galleries, such as Beckmann and Lyonel Feininger.

Two years after the museum opened, Muscatine businessman and philanthropist Roy J. Carver gave money toward a 13,000-square-foot addition to the UIMA that opened in 1976.

Stanleys’ support strengthens African art studies program

Mary Jo and Richard Stanley of Muscatine, Iowa, committed $10 million to support the building campaign for the University of Iowa Museum of Art. The gift comes from two generations of the family. Photo courtesy of the UI Center for Advancement.

One of Wilke’s greatest legacies to the university was his influence in inspiring museum patrons and UI alumni C. Maxwell Stanley and Betty Holthues Stanley to expand their knowledge and collection of African art. The Muscatine couple’s interest began in 1960 while visiting Liberia on a business trip for Stanley Consultants engineering firm, and under Wilke’s encouragement, the Stanleys began subscribing to art magazines and catalogs, visiting reputable galleries, and drawing the attention of top art dealers.

Over the years, they accumulated more than 800 ritual masks, religious figurines, and other pieces representing the finest African art in the United States.

The Stanleys’ commitment to give the collection to the UI Museum of Art prompted the School of Art and Art History to strengthen its African arts studies program. With the Stanleys’ support in 1978, UI School of Art and Art History Director Wallace Tomasini hired Christopher Roy as the Elizabeth M. Stanley Faculty Fellow of African Art History, becoming one of the first professors in the world to specialize in the field. In his almost 40-year UI career, Roy—who died in 2019—used the Stanley Collection in all of his classes to introduce hundreds of students each year to multiculturalism.

The couple passed their passion for the arts and the museum down to their children, who, along with their parents, would continue to prove influential patrons in the years to come.

Fleeing from a rising river

The museum’s artwork remained dry in 1993 when flooding of the Iowa River closed the museum for most of the summer. Yet the museum faced an even bigger challenge in June 2008 when a 500-year flood threatened the UI’s art campus. This time, it wouldn’t be a near miss.

About a week before the flooding, the Army Corps of Engineers warned the museum to prepare for an evacuation. Volunteers and staff scrambled to save the collection, beginning with the pieces of greatest value. After building crates for the works, staff loaded the masterpieces onto refrigerated trucks bound for a storage unit in Chicago. University vans took archival boxes filled with drawings and prints to the Old Capitol for safekeeping, while ceramics, jade, and sculptures were moved to higher ground within the museum.

On a notably unlucky Friday the 13th, floodwaters closed off all access to the museum. Though the museum didn’t lose any works of great importance in the disaster, it did lose its home of nearly 40 years.

Unlike some other campus buildings impacted by the flood, replacement of the museum did not qualify for Federal Emergency Management Agency funds because the building remained structurally viable for other purposes. However, the university was not allowed to exhibit UI and visiting art collections in the building due to immediate proximity to the Iowa River and related insurance limitations.

The Board of Regents, State of Iowa, approved building a new $50 million, 63,000-square-foot art museum adjacent to UI Main Library and next to Gibson Square Park. Funding for the new building—expected to open in 2022—will come from a mix of private support and bonds.

In December 2017, Richard (Dick) and Mary Jo Stanley, of Muscatine, Iowa, committed $10 million—a portion of which came from the estate of Dick’s parents, C. Maxwell and Betty—to support the building campaign for a new museum of art. In honor of the gift, the museum in April 2018 was renamed the University of Iowa Stanley Museum of Art.

Sharing Iowa’s art

Jackson Pollock’s Mural has been seen by nearly 2 million people during a whirlwind international tour of premier American and European museums:

• Des Moines Art Center (Iowa)

• J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles)

• Sioux City Art Center (Iowa)

• Peggy Guggenheim Collection (Venice, Italy)

• Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle (Berlin, Germany)

• Museo Picasso Málaga (Spain)

• Royal Academy of Art (London, England)

• Guggenheim Museum (Bilbao, Spain)

• Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, Missouri)

• National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.)

• Columbia Museum of Art (South Carolina)

• Museum of Fine Art (Boston, Massachusetts)

A documentary about the painting’s incredible history can be viewed via Iowa Public Television.

In the years without a building, the museum became more determined than ever to share Iowa’s artistic legacy with the university community, state, and world. Staff worked tirelessly to bring Pollock’s Mural and other cherished pieces before more eyes than ever before.

Iowans can still see select works from the museum at the Figge Art Museum in Davenport, Iowa, and in the Iowa Memorial Union’s former Richey Ballroom, now known as the Stanley Visual. Yet the collection also has become a source of pride in towns as far away as Sioux City through alumni events, the Stanley Museum’s “Legacies for Iowa” statewide collection-sharing program, Stanley School Programs for K–12 students, and the Senior Living Communities Program. The Stanley School Programs alone brought art education to 84,500 students across Iowa since 2008, and visited 21 counties, 32 towns, and 57 schools or other venues in the 2018–19 school year.

Pollock’s Mural, meanwhile, has been seen by nearly 2 million people during a whirlwind international tour of premier American and European museums.

Once the Stanley Museum opens a new permanent home for its collection, museum staff plans to maintain the statewide reach and partnerships it has developed in the years since the flood.

Among other projects, museum director Lessing says the museum hopes to bring educators from across the state to the museum for seminars focusing on topics such as object-centered learning in social studies.

“While we may not drive works of art to students like we have been doing, we can still serve those schools through teacher education,” Lessing says.

Lessing says museum staff are also thinking about their partnerships with museums across the state, including the Figge Art Museum in Davenport, Iowa, where much of the collection has been stored since the 2008 flood.

“We want to think about how our collections complement each other and how we can curate exhibitions that draw from both collections,” Lessing says. “Even while we’ll have a wonderful building and dynamic exhibition program, we can maintain a satellite presence at other museums. This will allow people to enjoy our collection without always having to drive to Iowa City.”

Marking artistic discoveries through research, conservation

Grant Wood’s Plaid Sweater (1931) was cleaned and treated by Rita Berg, paintings conservator at Midwest Art Conservation Center, in early 2018, prior to joining the Whitney Museum of American Art’s major retrospective on Wood later that spring. Photo courtesy of the Midwest Art Conservation Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

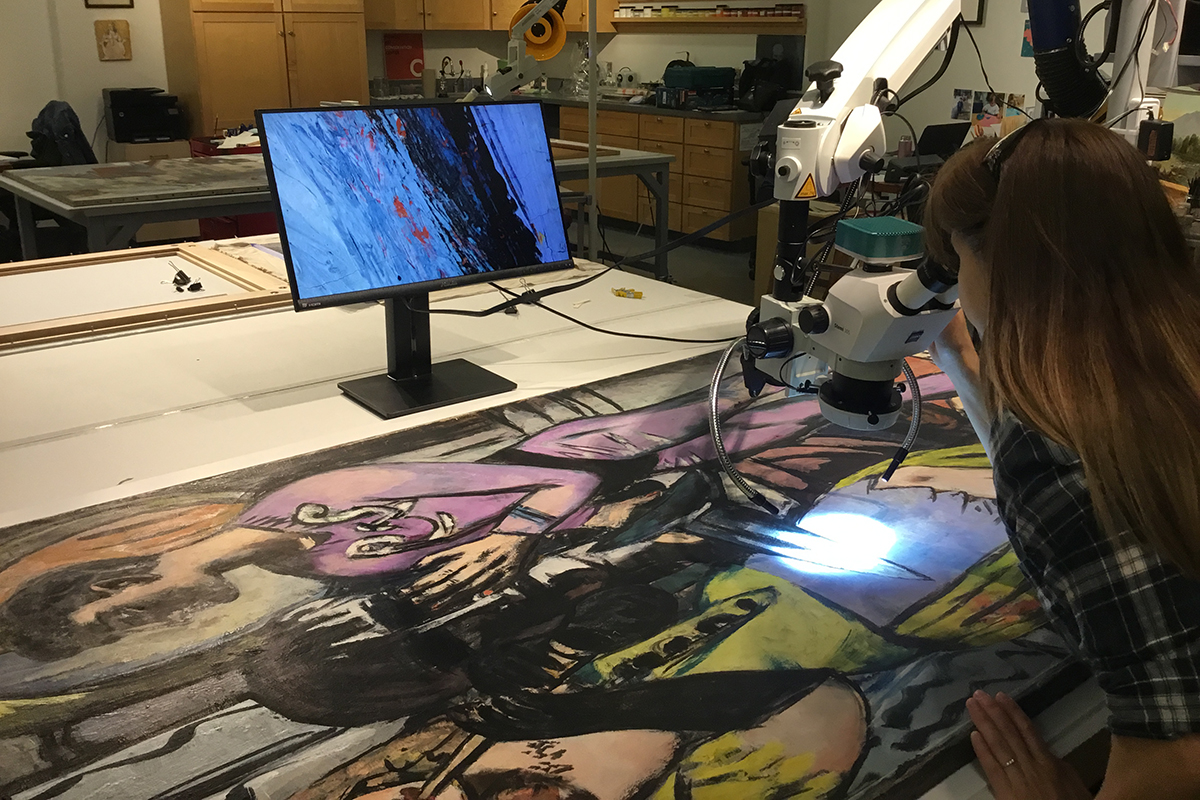

Conservation, preservation, and research have been important to the Stanley Museum’s mission since its inception. As the museum prepares to move into a new building, staff want to make sure key pieces can stand up to being on display and look as good as possible.

In some cases, this can simply—or as “simply” as anything can be when it comes to working with great works of art—mean cleaning and removing varnish. This was the case with Grant Wood’s Plaid Sweater. In the decades before it was gifted to the museum, its surface had accrued decades of dust and soot and the varnish had yellowed. The removal of dirt and the discolored varnish revealed a brilliant blue sky that hadn’t been seen since the early to mid-20th century.

Pollock’s Mural underwent a more extensive process. In 2012, the 8-foot-by-20-foot work was sent to the Getty Conservation Institute for two years of analysis, extensive cleaning, removing varnish, and remounting the canvas onto a new, curved stretcher to address sagging.

Conservation work also can reveal insights into how an artist created a masterpiece, as well as how to better preserve such objects. This was the case with Max Beckmann’s Karneval.

“Max Beckmann created Karneval while he was working in exile in Amsterdam during WWII,” Lessing says. “He didn’t have access to the best materials. He used whatever came to hand. So, through this conservation process, we’re learning fascinating things that are going to point museum professionals in directions that are better suited for the care of objects like the Beckmann.”

Beyond conservation, museum staff also are continually trying to learn more about the art in the collection. In early 2019, 16 of the museum’s works of African art were put in a computed tomography (CT) scanner at the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics to discover what was hidden inside the objects. This knowledge allows curators to better understand and explain the collection to future visitors to the museum.

“We plan to make what we discover in the CT scanning or about Mural or Karneval part of how we present those works when they go on display in the new building,” Lessing says.

Future of the Stanley Museum of Art

- 16,500 square feet of gallery space

- Art lounge

- Visible storage

- Three-story lightwell

- Visual classroom

- Underground parking

- Two outdoor terraces

When it opens in 2022, the Stanley Museum of Art will be the final structure to be rebuilt on the UI campus in the aftermath of the 2008 flood. While its mission will remain largely the same, the new building will differ in some ways from the original.

“We’re not just recreating what the museum was in 2008,” Lessing says. “Museums have completely shifted in the last decade from being elite institutions to being broad and populist institutions. From being places where you needed to speak in a very quiet voice to being sometimes loud and fun. We’re planning a reinstallation for this new way that museums function in the world.”

Lessing says museums worldwide are embracing new roles, and the Stanley Museum’s new home has been designed as a laboratory. Along with housing galleries to showcase UI’s renowned art collection, it will serve as an important educational resource for the campus and state.

In addition to being a place where visitors can experience artwork firsthand—as opposed to merely seeing it in a book or online—the Stanley Museum strives to serve as an incubator for interdisciplinary conversation and research.

Much of the content for this story originally appeared in a story written by Shelbi Thomas for Iowa Magazine.

“We want students and faculty from across campus to be fully invested and engaged in the museum,” Lessing says.

The museum also has been designed with flexibility in mind. The lobby, for example, will have an acoustic ceiling and a drop-down screen for concerts or presentations. It will have comfortable seating and electrical outlets allowing students, faculty, or community members to sit down and study or visit with each other.

“It’s not that there won’t be beautiful gallery spaces for quiet contemplation; that will always be part of our mission,” Lessing says. “But it will also have spaces for active learning for people of all ages, for classes, and for making.”

Through it all, the museum is charged with an interpretive responsibility as the world continually changes, says Steve McGuire, professor of metal arts and 3-D design and director of the School of Art and Art History.

“When a museum does an exhibit, they take what they have and what they know is out there in the world in terms of art and apply it to this particular moment in time,” McGuire says. “The value of the museum can’t be overstated. It is a vehicle to and from the wider world for the state and for the university.”