Undergrads learn resilience by conducting research

For decades, Robert Kirby has met with prospective students, coordinated with and trained faculty on mentoring undergraduate researchers, and collaborated with campus partners to expand access to and participation in campus research for undergraduate students.

“Research is just one of those tremendously important parts of what students are able to do at a place like Iowa,” says Kirby, adjunct associate professor of psychology and the director of the Iowa Center for Research by Undergraduates (ICRU). “People like to say that students involved in research have higher grade point averages and are more likely to graduate in four years, but what I like to highlight is that students involved in research are more likely to get to know a faculty member on campus. They’re more likely to raise questions in class. They’re more deeply engaged in their education and that’s going to benefit them in so many different ways.”

The UI Strategic Plan 2016-2021 outlines strategies and lists measures for success in three key areas:

- Research and discovery

- Student success

- Engagement

Read the full strategic plan, along with progress reports, on the University of Iowa strategic plan website.

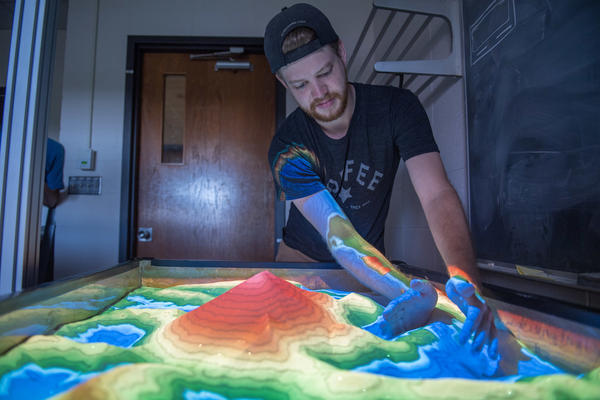

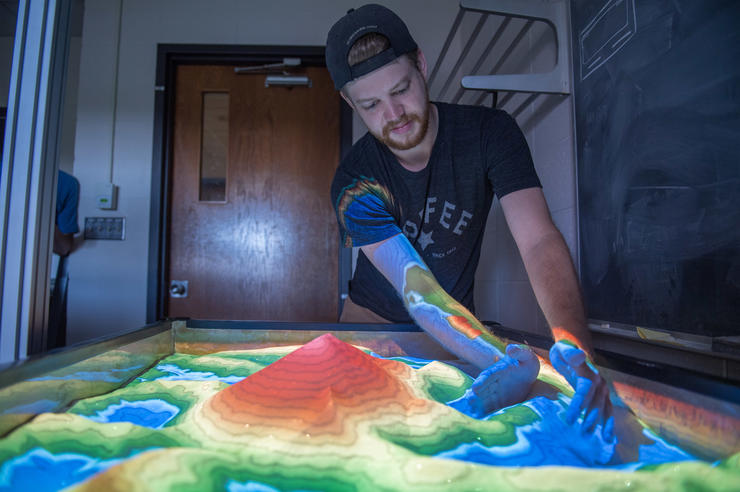

Kirby’s most recent efforts are the creation of new undergraduate seminars on research, which the ICRU steering committee—made up of faculty from numerous disciplines—helped design. He says that many students don’t consider research when they envision their college career, and he wants to help them see that research is within everyone’s reach because it involves asking questions more than filling test tubes.

“We ask so many questions when we’re young,” says Kirby, “and then we become too concerned with already known answers and we forget that discovering new answers is one of the most important things we can do.”

Even before he became the ICRU director in 2006, Kirby has connected undergraduates with faculty looking to mentor students in research. His many success stories include James Ankrum, a UI assistant professor of biomedical engineering, who first met Kirby in 2003 as a 17-year-old high school student touring campus.

Ankrum came to the UI from Eldora, Iowa, and was inspired by his father’s back pain to study the effects of large machinery vibrations on the human body, attempting to discover whether people who drive cars, trucks, or tractors all day suffer any negative effects. He went on to receive a master of philosophy at the University of Cambridge and a PhD at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, after which he returned to the UI and now conducts research in the Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center at the UI’s Pappajohn Biomedical Discovery Building.

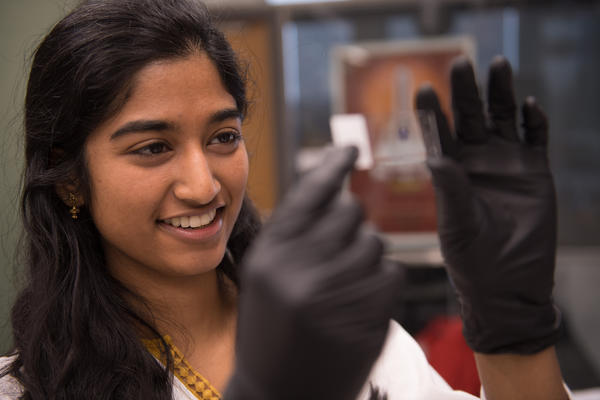

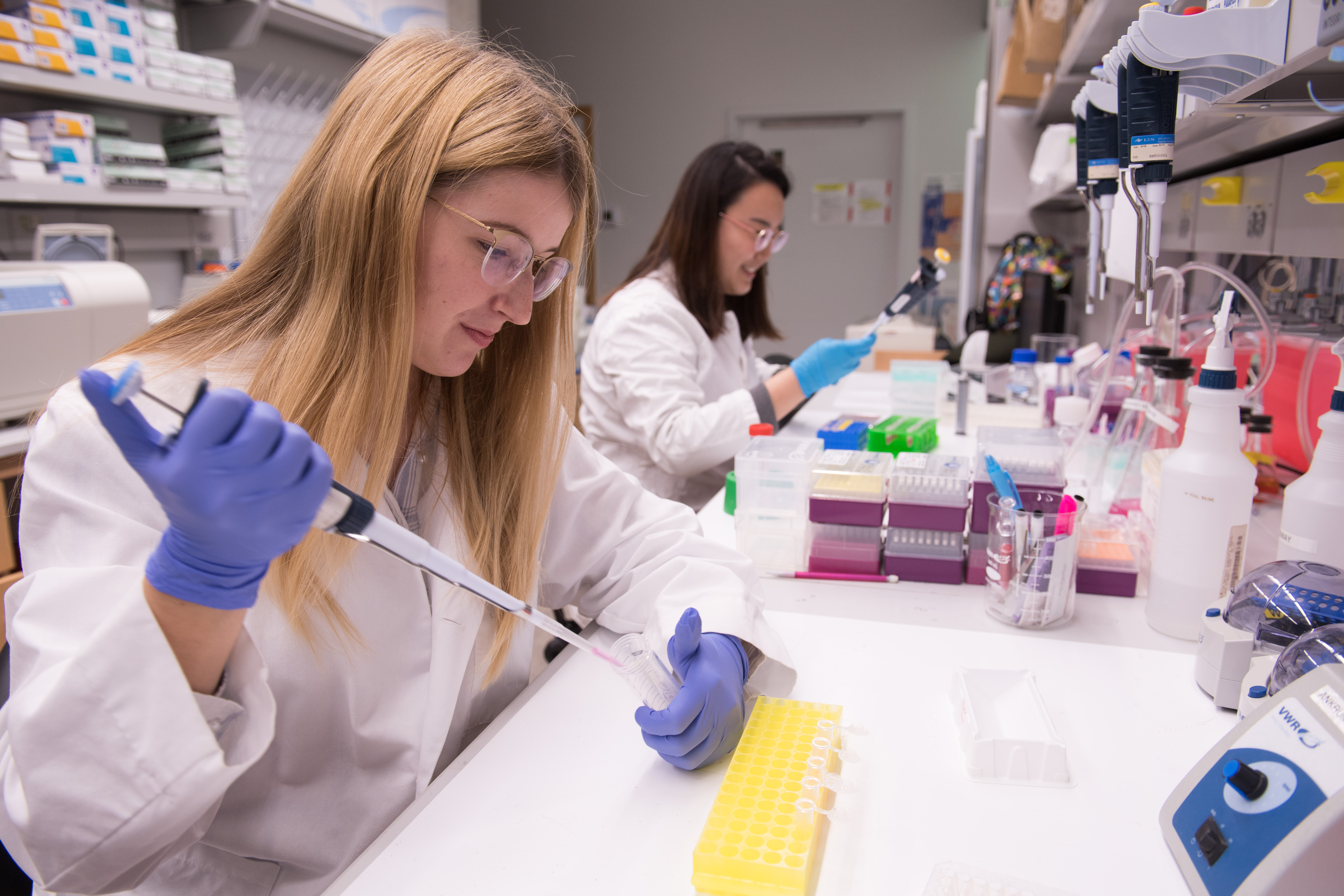

Ankrum supervises five undergraduates, four graduate students, and one postdoctoral scholar as he investigates the possibilities of using live cells as therapeutic agents for people suffering from diabetes.

“If we’re going to help our students here at Iowa become top-tier candidates, then they need to have opportunities to experience what research actually is,” says Ankrum. “And you get that by actually being in a lab day-in and day-out, experiencing the joys, the setbacks, and the confusion that is inherent to any kind of research as you try to discover what nobody else has seen before.”

Kirby says about 30 percent of undergraduates at the UI conduct or assist research. According to the UI strategic plan, research is considered a high-impact practice (HIP), which the plan defines as programs that require students to integrate learning across contexts. These programs help students extend what they learn in college to the challenges they may face later in life.

The strategic plan also considers service learning, internships, writing-intensive courses, academic campus employment, and other activities, to be HIPs. The strategic plan sets a goal for increasing the number of undergraduates who participate in at least three HIPs before they graduate to 60 percent.

Third-year undergraduate Isabella Penniston, a nursing major from Bellevue, Iowa, is on track to graduate in spring 2020 and already has three HIPs under her belt. She works as a nursing assistant at the UI Hospitals & Clinics, participated in the India Winterim study abroad program in 2017, and is currently conducting and assisting research into the effects of tele-communication interventions on the mental health of rural Iowans battling cancer.

Penniston works under the mentorship of Stephanie Gilbertson-White, assistant professor in the College of Nursing, who studies internet mediated interventions that are designed to help cancer patients manage their symptoms.

Penniston says her experience in undergraduate research surprised her.

“A lot of people will look at cancer patients and automatically take pity on them,” says Penniston, “but I discovered that a lot of cancer patients don’t see it that way, which was really eye-opening for me. It helps me when I’m in the clinic to know that, yes, this person has a disease, but the person themself is not their disease.”

In addition to gaining valuable insights, Penniston says that working in a lab with a team of fellow researchers—people who are not her peers or teachers—has taught her to be more self-directed.

“Research has just made me better at prioritization,” she says. “It’s made me more organized and responsible, because when you have a team of people depending on you and when you have your own project that needs to be done, it’s critical that you have those kinds of skills. I think, overall, research made me into a better student, and I think it will make me into a better nurse one day.”

Penniston presented preliminary findings of her research at the UI’s Ninth Annual Fall Undergraduate Research Festival on Nov. 14 and this spring she will present her full findings at the Midwest Nursing Research Society annual conference in Kansas City, Missouri.

Kirby says that making sense of research findings can be challenging for undergraduates because the results often are unexpected, which can be frustrating.

“A lot of us who work closely with undergraduate students can see that dealing with setbacks is something that they’ve had limited experience with,” says Kirby. “How do you solve problems, and when you have a setback, how do you move forward? Our students have had great success throughout high school, they’ve been able to go on to college, and they’re doing well here, but in research a high percentage of your studies is not going to turn out the way you expect.”

Ankrum agrees.

“You’re going to run into your fair share of walls,” he says.

Penniston says she felt frustrated and hopeless when her research data didn’t match her initial hypothesis.

“It felt like a lot of the work I’d done wasn’t amounting to much,” says Penniston. “(Professor Gilbertson-White) encouraged me to look outside of the box I’d created for my research. Although the results I obtained didn’t fit my original research idea, she encouraged me to look at what the results could tell me. Thanks to her help, I was able to develop a new hypothesis and question for my research that’s just as strong, if not stronger, as my original idea.”

While finishing his PhD, Ankrum sat on MIT’s admissions committee and evaluated prospective graduate students. He says the ability to experience a setback and persevere is a good indicator of a student’s future success, in part because successful research sometimes illuminates the limitations of previous research.

“If we’re going to help our students here at Iowa become top-tier candidates, then they need to have opportunities to experience what research actually is. And you get that by actually being in a lab day-in and day-out, experiencing the joys, the setbacks, and the confusion that is inherent to any kind of research as you try to discover what nobody else has seen before.”

As an example, Ankrum explains that a lot of his research into living cells has been conducted in two dimensions, meaning cells were grown on a flat surface. But recent developments allow researchers to grow cells in three dimensions, more similar to the shape of organs, and results show that these cell cultures act differently than those grown in two dimensions. This raises the question of the validity of previous findings, some of which took years to complete. Such a discovery can be a daunting moment for a researcher.

“The question I ask day-to-day is ‘How can you be inquisitive and ask questions that actually challenge your previous work?’” says Ankrum. “Having the drive, and building that inquisitive nature, to really ask hard questions that will push you forward is really powerful.”

Ankrum not only encourages other UI faculty to mentor undergraduate researchers, he has published an article in Nature science journal sharing his experience. Ankrum says the article received millions of views and was shared on Twitter more than 700 times.

Ankrum says that there is a debate in academia about the value of getting a degree on a campus versus getting an online degree. To him, undergraduate research is part and parcel of why students should attend college in person. He says that if he had stayed in his hometown of Eldora, Iowa, he never would have found his career.

“The University of Iowa has every opportunity that you would need to really see what the world has to offer,” says Ankrum. “It can be a launching pad into a lot of different careers, but it’s one of those things where you have to come in and accept the challenge—and it will be a challenge. There are resources and people who will help you succeed and continue pushing you to grow to your full potential if you’re willing to place yourself into some of these unknown places.”

Get involved in life-changing research. Join the Hawkeye Family, today.