Rare find punctuates undergrad’s research experience

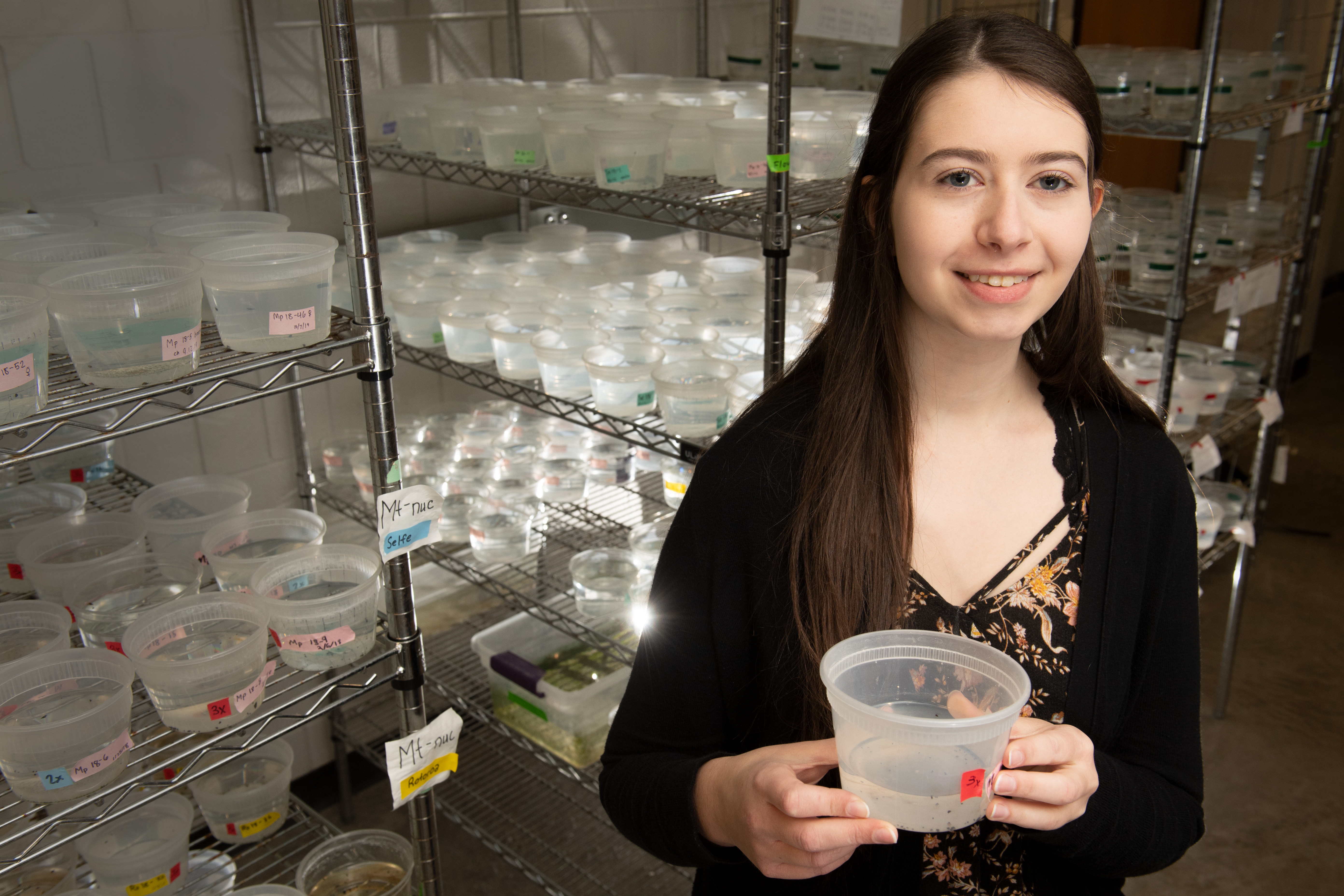

Marissa Roseman never thought her research experience would lead to her feeling affection for a lab specimen.

But then again, she didn’t expect the specimen to be a one-in-a-million discovery.

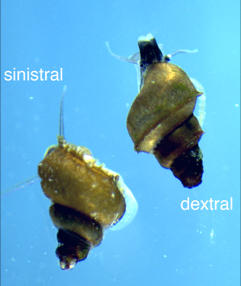

Roseman, a University of Iowa senior majoring in biology and environmental sciences, was doing her usual routine of cataloging lineages of New Zealand freshwater snails used by UI biologist Maurine Neiman to study sexual and asexual reproduction in animals, when she noticed one female snail’s shell was coiled to the left.

New Zealand freshwater snails almost universally coil to the right. Finding one whose shell spirals left is considered to be a rare discovery, akin to finding a blue lobster in the ocean.

“It’s definitely one of the most exciting things found in my lab,” says Neiman, associate professor in the Department of Biology who has studied New Zealand freshwater snails for two decades. “I get a kick out of going and looking at her.”

Scientifically, the snail—which the research group calls “Sinistra,” meaning “left” in Latin—could help biologists better understand how genetics, mutations, development, and the environment determine whether organisms, their organ systems, and even their body parts are or are not symmetrical.

New Zealand freshwater snails almost universally coil to the right (dextral in Latin). University of Iowa undergraduate researcher Marissa Roseman discovered an extremely rare left-coiling (sinistral) snail during her lab work. The find is considered a one-in-a-million occurrence.

Roseman is still coming to grips with the randomness of her find.

“I do think it’s a lottery in the sense that it is a chance discovery,” says Roseman. “Anybody could have discovered this. I just happened to be the one.”

One could say Roseman’s involvement in Neiman’s lab, too, came somewhat by chance.

Roseman matriculated at Iowa in the fall of 2016 as a Presidential Scholar. She described her interest in environmental justice issues to Bob Kirby, who runs the Iowa Center for Research by Undergraduates, who urged her to get involved in research. From that meeting, Roseman perused biology faculty websites, then told Kirby she was interested in Neiman’s research. Kirby arranged a meeting.

It didn’t take long for Roseman to decide she had found a research home.

“I could immediately tell (Neiman) is someone who is a really great mentor, really involved with her students, and really passionate about her research,” Roseman says. “She’s excited about connecting students with research, and that was something I was really looking for.”

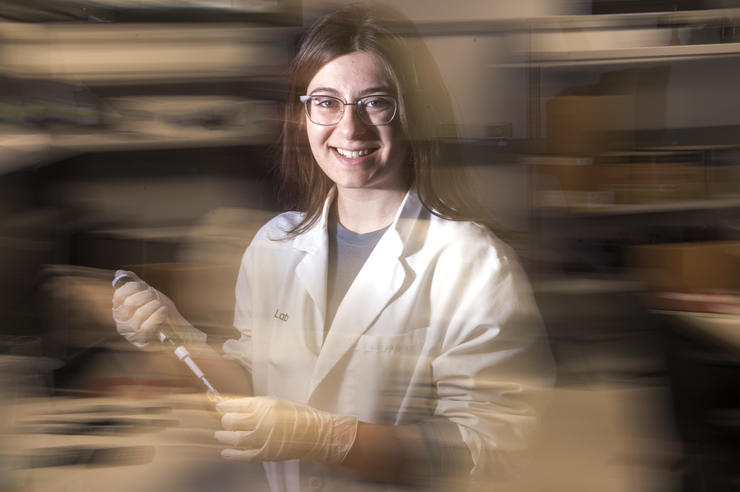

Neiman started Roseman with an ambitious undertaking: Label individual snails’ DNA using a $100,000 machine that performs flow cytometry, a technique that utilizes light to count and profile cells in a fluid mixture. The purpose was to identify sexual and asexual snails by the amount of dye that stuck to each snail’s DNA; because asexual snails have more DNA, they capture more dye and glow more brightly.

“You have to do this correctly. You’re often working with irreplaceable samples,” Neiman says. “And you’re working with an expensive machine that you don’t want someone in your lab to use carelessly. We entrusted her with it pretty quickly, and she did great.”

The summer after Roseman’s sophomore year, Neiman charged her with launching a project funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF). The ongoing research involves generating genetic data that can be used to study how proteins in mitochondrial and nuclear genomes pair up to use oxygen efficiently, which of course is essential to an organism’s ability to live.

Roseman led a small team that raised thousands of snails and their offspring. From that batch, Roseman isolated hundreds of females whose mitochondria (the genes of which are passed down only by the mother) could be studied in detail.

“Literally, Marissa is running a big branch of a major research project. I wouldn’t get anything done without undergraduates like her.”

“It was a tremendous amount of work,” Neiman says. “You know, I got the funding for this project, and I didn’t really have a graduate student to run it, and I was like, ‘Now what?’ And, thankfully, I had Marissa.”

In all, Roseman says she’s supervised about 20 high school and fellow undergraduate students during her time at Iowa. She says being mentored and then training others has been one of her most memorable research experiences to date.

“They showed me how you can take someone under your wing and help them become a better researcher,” Roseman says. “As I’ve spent more and more time in the lab, I think that’s something I’ve learned to do myself. I’ve worked with a lot of other students and helped them get involved in my projects, helped teach them different skills in the lab, and that’s been something really important to me.”

For Neiman, Roseman’s leadership underscores the value of involving undergraduates in high-profile research.

“Literally, Marissa is running a big branch of a major research project. I wouldn’t get anything done without undergraduates like her,” Neiman says. “It’s not just their work, either. They add perspective. They come in with fresh perspectives. They can be creative and open-minded in ways that are difficult when you have preconceived notions about how biology should work because you’ve been doing it for a long time.”

Roseman parlayed her efforts into landing a Research Excellence for Undergraduates award from the NSF. The award sent her to the University of Notre Dame last summer, where Roseman helped assess how cover crops could be used to improve water quality in agricultural watersheds.

It was when she returned to campus in August that she made her surprise snail discovery.

“I think my first reaction was disbelief: Is this actually what I’m seeing? Is it just bent on its side or something?” Roseman recalls. “I had to zoom in and get a better look at it, sort of like pick it up and turn it over, and say, ‘Yes, this is what I think it is.’”

She hustled over to Neiman’s office, excited but still not completely sure of her discovery.

“Marissa said, ‘It’s coiling the wrong way,’” Neiman says, “My first reaction was ‘No way.’ But then I looked at it, and thought, ‘Holy smokes, it really is.’ Marissa looks through thousands of these cups every week, and you have to scan them quickly to get done what needs to be done,” Neiman adds. “So, I was really impressed that she noticed it.”

While most left-coiling snails die without having offspring (as they can’t position themselves to successfully mate with snails coiling to the right), Sinistra is asexual, which means she doesn’t need to mate to reproduce. Neiman’s team is excited to study her offspring, which will be genetic clones, to further understand how left-coiled snails came to be.

That puts Roseman front and center in making sure Sinistra is content.

“To a degree, it does feel motherly,” Roseman says with a smile. “This is something I’m invested in, that I care about.”