A researcher, a teacher, a leader

Craig Kletzing came to the University of Iowa in no small part because he wanted to teach.

In 1995, Kletzing was on the research faculty at the University of New Hampshire, with limited teaching opportunities. But he wanted to teach physics—all sorts of physics—in addition to performing research.

He learned of an open faculty position at the UI through Jack Scudder, professor in the UI Department of Physics and Astronomy, who was collaborating with Kletzing on a NASA mission to study the flow of particles that cause auroras.

Kletzing applied, got the job, and has been happily combining his research interests and passion for teaching ever since.

“I always knew I wanted to be teaching in a physics department,” says Kletzing, who joined the UI in August 1996. “I would’ve stayed as a research scientist if I didn’t like teaching so much. I like the mix of the two.”

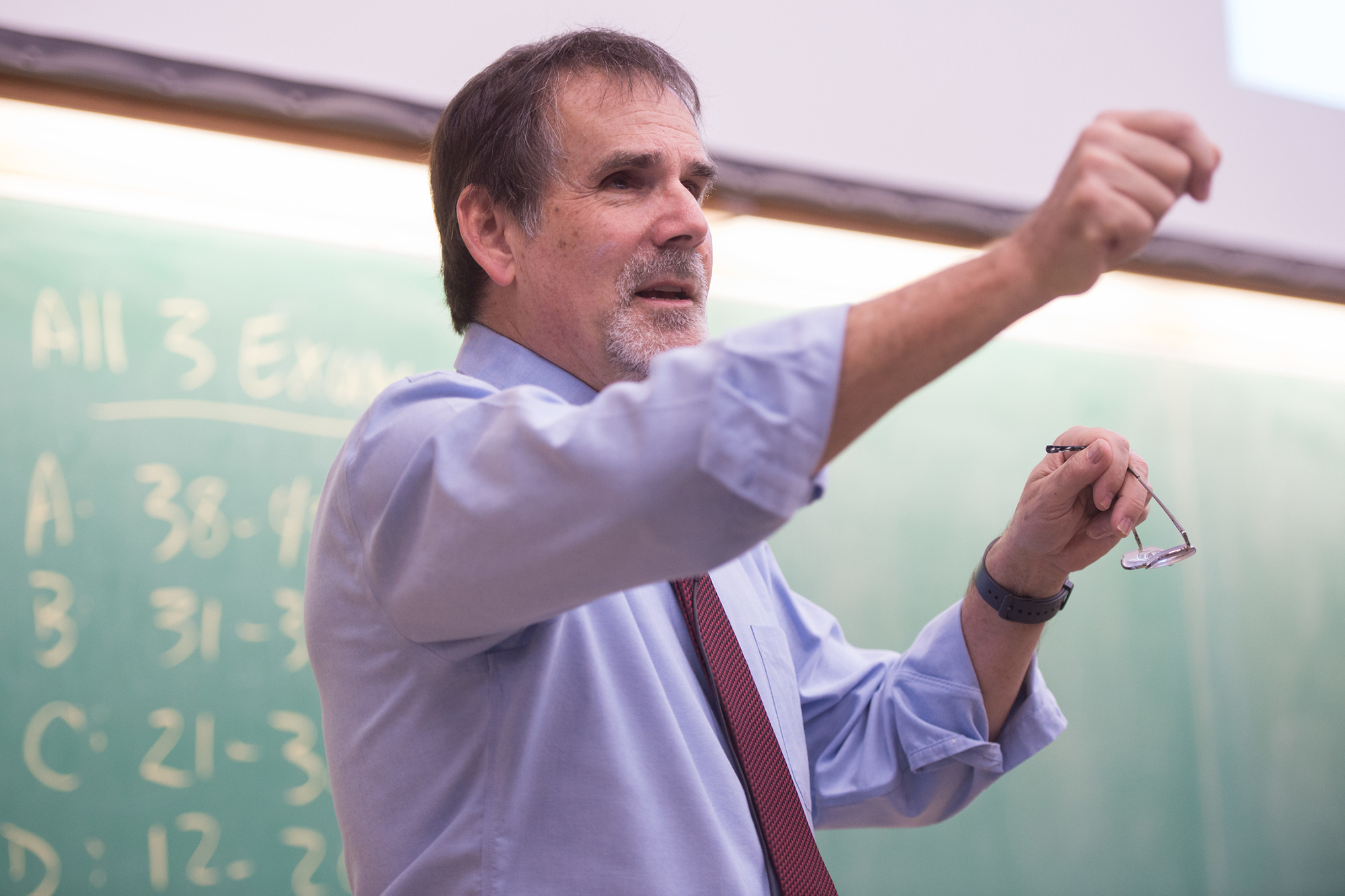

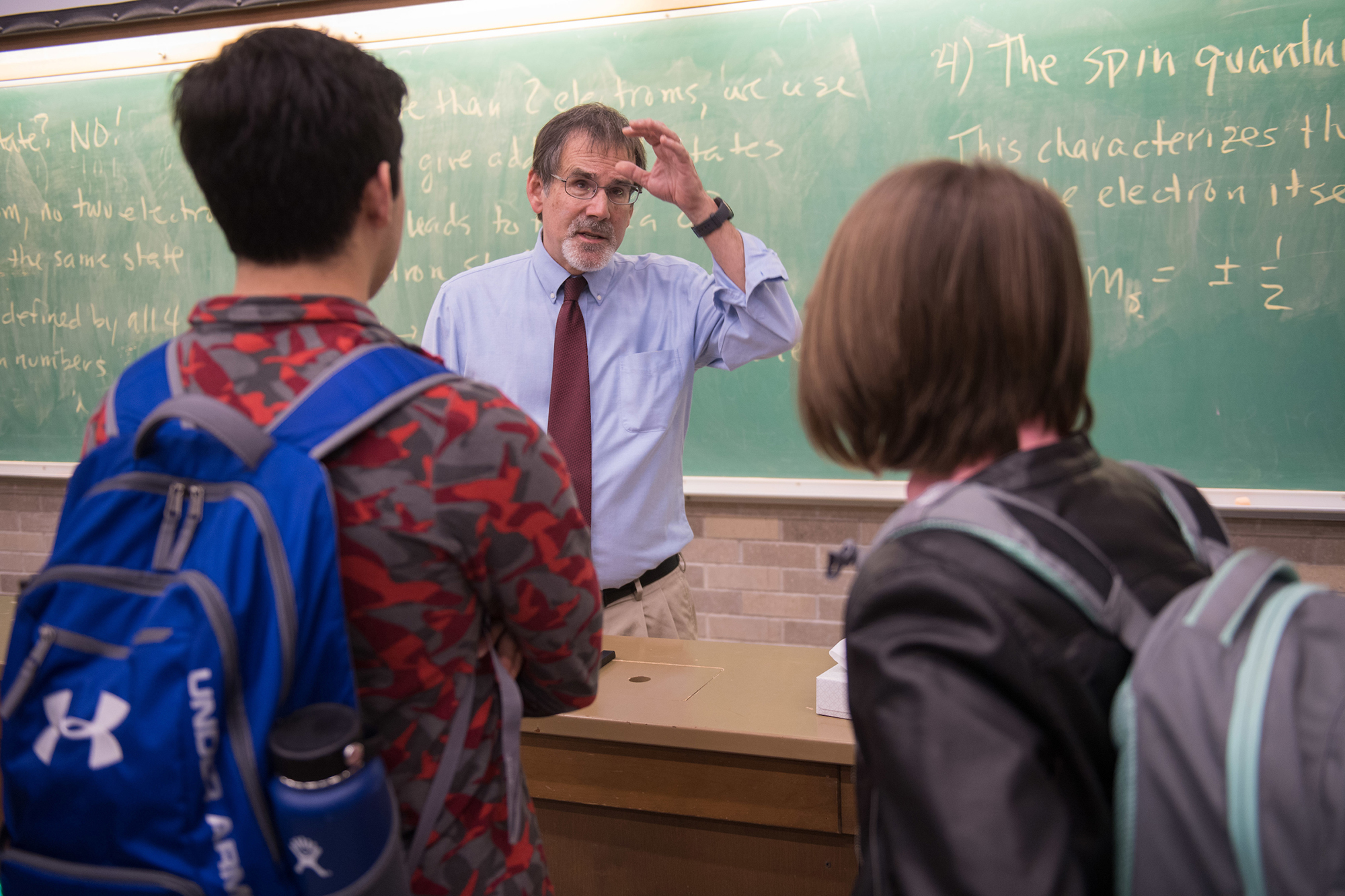

True to his interests, Kletzing has taught a broad range of classes in the department, from introductory classes for non-physics majors to advanced courses for physics majors. A rocket scientist with a flair for the dramatic, he’s well known for his in-class demonstrations: one involved UI President Bruce Harreld riding a rocket-powered tricycle; another explained Archimedes’ principle of buoyancy with a pail of water and a rock.

“I find teaching rewarding,” says Kletzing. “It’s explaining things that I think are interesting to other people and letting them see what some of the interesting part of it is all about. There’s satisfaction when students who are struggling a bit suddenly get it. Plus, as I get older, I just like being around younger people. It’s the interest and passion that young folks have. I find that enlivening and a rewarding thing to be around.”

A team led by University of Iowa physicist Craig Kletzing has won $115 million from NASA to study the mysterious, powerful interactions between the magnetic fields of the sun and Earth.

The contract award is the single largest externally funded research project in UI history. Out of more than 35,000 projects awarded to the UI since 1965, Kletzing’s contract is the only research award of more than $100 million.

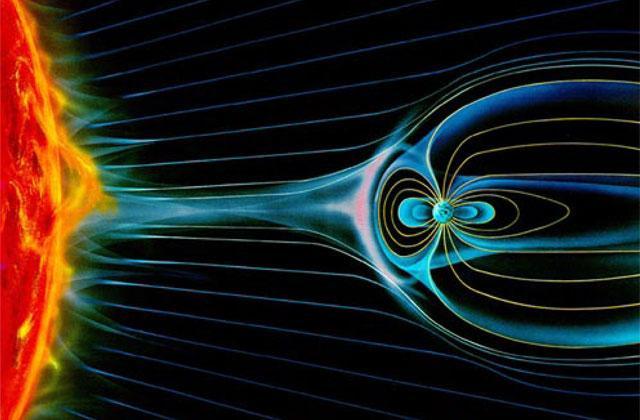

Kletzing’s research has blossomed as well. In June, he won a $115 million contract award from NASA—the largest single award in UI history—to realize a mission, called the Tandem Reconnection and Cusp Electrodynamics Reconnaissance Satellites (TRACERS), to study the mysterious, powerful interactions between the magnetic fields of the sun and Earth that trigger auroras and other space phenomena.

“This is a career milestone for me, personally,” Kletzing says. “It’s also a fantastic opportunity to do some really great science with an all-star team.”

Kletzing became intrigued with the physics surrounding auroras as an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley, at the time a hub of auroral physics. His involvement led to his first published research paper—and grander designs about his involvement as a scientist.

“I could stay and work for somebody writing code, or go do it for myself,” Kletzing says.

Kletzing earned master’s and doctoral degrees in physics at the University of California, San Diego, under the wing of Carl McIlwain, a professor and experimental physicist who studied under UI legendary physicist James Van Allen. Kletzing was especially interested in the relationship between auroras and Alfven waves, a type of plasma wave that causes electrons to accelerate and crash into Earth’s atmosphere, creating auroras.

“It’s just some really interesting physics,” Kletzing says. “I mean, there’s the natural beauty of auroras, but to be frank, what really pulled me into it was the physics of what’s going on and how the auroral particles are created.”

“I like the university, and the work I do here. There aren’t that many universities that have the technical infrastructure to build these types of experiments.”

Kletzing’s involvement in auroral physics stretches from multiple forays building and flying sub-orbital sounding rockets over active aurora to leadership roles on satellite missions in the chaotic envelope where the Earth’s magnetosphere collides with space.

“I like the university, and the work I do here,” he says. “There aren’t that many universities that have the technical infrastructure to build these types of experiments.”

Kletzing’s research profile rose further when his team landed a science spot on NASA’s Van Allen Probes. That mission, named after the UI’s Van Allen and which launched in 2012, involves two satellites that swoop in and around the Van Allen radiation belts, two extreme and dynamic regions of space that surround Earth. Kletzing is the principal investigator on Electric and Magnetic Field Instrument Suite and Integrated Science (EMFISIS), an instrument that focuses on the magnetic fields and plasma waves in the region.

“I really hadn’t done much radiation belt physics,” Kletzing says, “but being an experimental physicist, I knew we could build the right instruments.”

He also is an investigator on a more recent mission, the Magnetospheric Multiscale, or MMS, which launched in 2015. The science being gathered on MMS complements what Kletzing and other scientists hope to learn from the TRACERS expedition.

In that regard, Kletzing continues the legacy conducting experiments in space with in-house designed and built instruments that defined Van Allen’s career.

“I’m hardly the first person to do this, but that’s kind of why I was hired, to keep this field of research going,” Kletzing says. “So, I’m happy I’ve been able to do so. It’s not easy. It’s a competitive game.”

He’s even happier with the university administration’s support of recent hires of space physics experimentalists in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, including Casey DeRoo, Jasper Halekas, Allison Jaynes, and David Miles.

“I am exceedingly pleased with the people we’ve hired because I can sail off into the sunset someday and know it will keep on going here,” Kletzing says. “We have some great faculty.”